Dracut man cultivates cannabis career

BOSTON — Two years ago, Phil Hardy lost his job at Raytheon and re-purposed most of his Derry, N.H., home into a marijuana-cultivation facility.

He’d been growing cannabis since he was 16, when he kept plants in hidden niches of his parents’ home, and by 2014 he was well-known in the Merrimack Valley for a strand he’d christened Derry Dank.

The notoriety started to reach the wrong ears, though, and Hardy, who now lives in Dracut, was forced to abruptly tear down his operation and sell the house. He found himself essentially homeless.

But life today is very different.

“I was always a hard worker and I feel like this weekend is where it all paid off,” Hardy said, as he stood in a cordoned-off VIP only area of Boston Common Sunday.

Phil Hardy of Dracut hangs an American flag on the main stage of the Boston Freedom Rally on Boston Common Sunday. Above him is a banner for his company, The Hardy Consultants. To his left, is a banner for Social High, a marijuana social networking website Hardy is a partner in. sun/todd feathers

Outside the temporary barriers, thousands of pipe-toting, joint-rolling, candy-eating marijuana afficionados, political activists, and entrepreneurs were congregating for the second day of the Boston Freedom Rally, Massachusetts’ largest cannabis festival.

And Hardy, as chair of the entertainment committee, was very literally running the show.

The slender 33-year-old, in baggy blue jeans and a black shirt stamped with a neon green “T.H.C.” (an acronym for his company, The Hardy Consultants) was feeling the stress, but outwardly he seemed impossibly calm as he organized security, tracked down wandering rock n’ rollers, and networked like a Harvard business school senior.

“A festival like this, an event like this, is a perfect example that stoners can be successful,” Hardy said. “Everyone’s wired differently. If someone lacks motivation, that’s on them.”

Hardy’s mother died of cancer when he was 9 and his brother-in-law, Brian Kinney, died in the terrorist attack on Sept. 11, 2001.

Hardy is a self-confessed emotional guy and amid the bustle of a festival that could make or break his reputation, mentioning his mother, his brother-in-law, and his father’s health problems brings Hardy to tears.

Phil Hardy, of Dracut, produces a blunt with 20 grams of marijuana in it from the RV that served as the headquarters for the Boston Freedom Rally’s entertainment committee on Sunday. sun/todd feathers

Those deaths he experienced at such a young age heavily influenced the path his life would take.

He turned seriously to marijuana to cope with his brother-in-law’s death on Sept. 11, and now, as a marijuana consultant, he doesn’t accept payment when he sets up a medical-marijuana home-grow for someone battling cancer.

“He helps everyone he comes in contact with and gives back,” said Philip Scangas, a producer at WAAF radio, who was one of the first people to encourage Hardy to pursue a career as a marijuana consultant. “I’ve never seen someone take more advantage of opportunities … He’s not intimidated by it. A lot of people are intimidated by what this is.”

What the Massachusetts cannabis community is right now is a world in flux.

Phil Hardy, right, gives VIP access wristbands to Oli Herbert, the guitarist for All That Remains. sun/todd feathers

While the polls remain tight, there is a very real chance that voters will legalize marijuana for recreational use in November.That has prompted an explosion of entrepreneurial energy. Mixed in with the dozens of booths selling glass bongs and hemp Bob Marley shirts at the Boston Freedom Rally were vendors advertising hemp seed “wonder drugs,” industrial extraction ovens, and dozens of other products that could transform what it means to be a stoner.

Hardy has gotten in on the ground floor and become a recognizable figure in the industry.

In the space of two years, beginning with his rapid escape from the Derry house, he built up his consultancy; became a partner in Social High, a marijuana social network; was named to the board of directors of MassCann, the state’s primary advocacy group; and is now on the verge of signing a seven-figure contract to oversee growing operations for a string of new medical dispensaries.

Everywhere Hardy ran on Sunday — and he did run — people knew him, and needed to talk to him. And those connections helped him to secure several large sponsors for the Freedom Rally, bolstering the event and further polishing the image Hardy is cultivating for himself.

“Phil’s just a really good guy and it shows in his sincerity and his honesty, because this business is tough,” said Joe Girouard, a serious, sun-glassed businessman whose company, Boston Smoke Shop, spent more than $30,000 to help sponsor the Freedom Rally. “You’re fighting people who don’t like it, you’re fighting people who are trying to extort it. More professional people are coming in now, when before it was just people trying to make money.”

Hardy smoked his share of marijuana Sunday (at one point, he casually produced a foot-long blunt), but it was clear that he was also high on a different aspect of the event.

He introduced his mentors, he introduced the people he’s mentoring. He clasped hands with rappers, rock stars, and national players in the marijuana movement. He talked about how he’s had to turn down offers to invest in his projects.

It’s a pretty good place to be for a pot-head who used to pump gas at Kinney’s Texaco station in Lowell.

“His interest is there, and as long as his interest is there I’ll support him,” said Paul Hardy, Phil’s father. “He’s very, very passionate about what he believes in.”

The rest of the family doesn’t necessarily feel the same way, and it remains a cloud over Hardy’s rapid success. But being surrounded by 10,000 people who also feel that, after decades of being misunderstood, they are now months away from triumph seems to be the right medicine for his regrets.

“When I found this community two years ago, I found my family,” Hardy said. “I fit in.”

Follow Todd Feathers on Twitter and Tout @ToddFeathers.

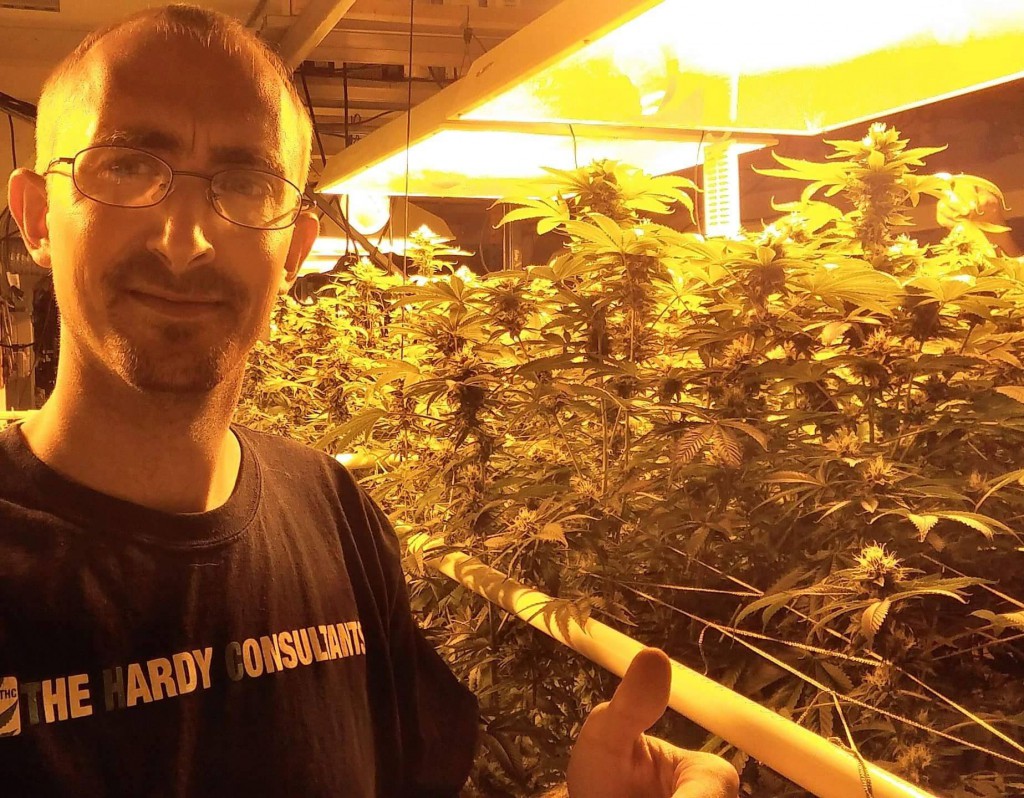

One of the grows I have visited on my trips to California during my trip to the Chalice Cup festival

The Hardy Consultants in California 2016. training in commercial grow spaces. 15 years ago I was taught misinformation about this plant and decided to investigate for my self what was so bad. Never would I have thought that this plant was going to take me for the ride of my life. The truth and science has spoken. Its time to reschedule this plant that causes no harm, but in fact has proven to do more good for ones health.